Ultrafast Lasers Create 3-D Crystal Waveguides in Glass

source:photonics.com

release:Julie

keywords:UltrafastLasersWaveguideFemtosecond

Time:2015-06-15

Femtosecond laser pulses can create complex, single-crystal waveguides inside glass – a discovery that could enable photo

nic integrated circuits (PICs) that are smaller, cheaper, more energy efficient and more reliable than current networks that use discrete optoelectro

nic components.

Using lanthanum borogermanate (LaBGeO5), researchers at Lehigh University have reported creating waveguides with a loss of 2.64 dB/cm at 1530 nm.

"Other groups have made crystal in glass but were not able to demo

nstrate quality," said professor Himanshu Jain. "With the quality of our crystal, we have crossed the threshold for the idea to be useful. As a result, we are now exploring the development of novel devices for optical communication in collaboration with a major company."

Waveguide

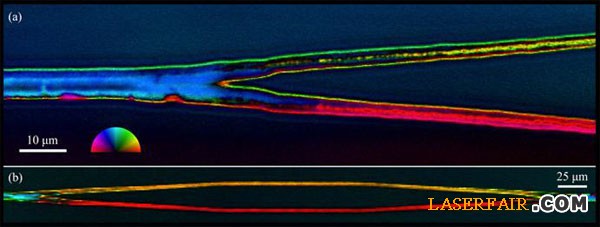

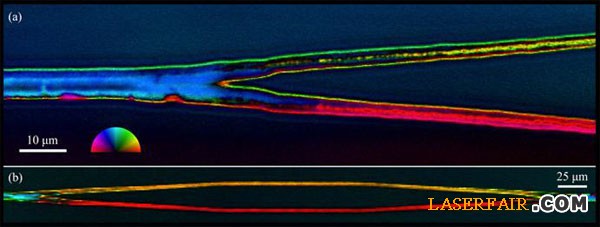

A polarized light field microscope image shows crystal junctions written inside glass with a femtosecond laser. Upon divergence (a), independent lattice orientations develop in each branch and are retained (b) as the branches merge back into a single line. The color wheel indicates the angle of the fast or slow axis of birefringence. Courtesy of Lehigh University.

The fabrication technique involves focusing femtosecond pulses inside a glass substrate to selecively melt regions and turn them into crystal. Dynamic phase modulation allows growth of symmetric crystal junctions with single-pass writing, the researchers said.

"We have made the equivalent of a wire to guide the light," said professor Volkmar Dierolf. "With our crystal, it is possible to do this in 3-D so that the wire – the light – can curve and bend as it is transmitted. This gives us the potential of putting different compo

nents on different layers of glass."

Photolithographic and other processes currently used for fabricating PICs are suitable o

nly for planar geometries. To fabricate 3-D PICs, the researchers said, it is necessary, first, to prevent light from scattering as it is being transmitted and, second, to transmit and manipulate light signals fast enough to handle increasingly large quantities of data.

Glass, an amorphous material with an inherently disordered atomic structure, cannot meet these challenges, but crystals, with their highly ordered lattice structure, have the requisite optical qualities.

Scientists have been attempting for years to make crystals in glass in order to prevent light signals from being scattered, Jain said. The task is complicated by the "mutually exclusive" nature of the properties of crystal and glass. Glass turns to crystal when it is heated, he said, but it is critical to co

ntrol the transition.

"The questions are, how long will this process take, and will we get one crystal or many," Jain said. "We want a single crystal; light cannot travel through multiple crystals. And we need the crystal to be in the right shape and form."

The fact that the demo

nstration was achieved using LaBGeO5, a ferroelectric material, creates additio

nal possibilities, Dierolf said.

"Ferroelectric crystals have demo

nstrated an electrical-optical effect that can be exploited for switching and for steering light from one place to another as a supermarket scanner does," he said. "Ferroelectric crystals can also transform light from one frequency to another. This makes it possible to send light through different channels."

The research was published in Scientific Reports (doi: 10.1038/srep10391).

MOST READ

- RoboSense is to Produce the First Chinese Multi-beam LiDAR

- China is to Accelerate the Development of Laser Hardening Application

- Han’s Laser Buys Canadian Fiber Specialist CorActive

- SPI Lasers continues it expansion in China, appointing a dedicated Sales Director

- Laser Coating Removal Robot for Aircraft

PRODUCTS

FISBA exhibits Customized Solutions for Minimally Invasive Medical Endoscopic Devices at COMPAMED in

FISBA exhibits Customized Solutions for Minimally Invasive Medical Endoscopic Devices at COMPAMED in New Active Alignment System for the Coupling of Photonic Structures to Fiber Arrays

New Active Alignment System for the Coupling of Photonic Structures to Fiber Arrays A new industrial compression module by Amplitude

A new industrial compression module by Amplitude Menhir Photonics Introduces the MENHIR-1550 The Industry's First Turnkey Femtosecond Laser of

Menhir Photonics Introduces the MENHIR-1550 The Industry's First Turnkey Femtosecond Laser of Shenzhen DNE Laser introduced new generation D-FAST cutting machine (12000 W)

more>>

Shenzhen DNE Laser introduced new generation D-FAST cutting machine (12000 W)

more>>